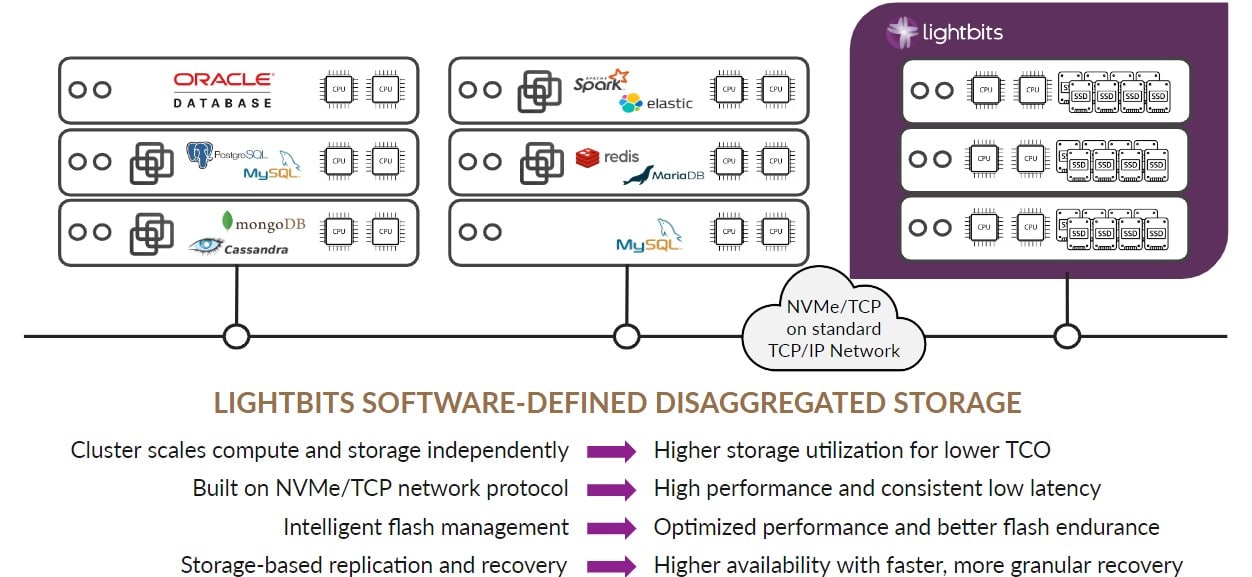

In most cases, cloud-native applications like NoSQL, in-memory, and distributed databases require low latency and high bandwidth, consistent response times, and recommend local flash (preferably NVMe®) for high performance. [Figure 1] In most cases, direct attached storage (DAS) over iSCSI is what is deployed to support these applications, as the deployment model delivers those needs. However, while there are some benefits, there are also DAS disadvantages, such as poor flash utilization, long recoveries in the event of a failure, and poor application portability.

Direct Attached Storage (DAS) Advantages

– High availability

– High access rate due to the absence of a storage area network (SAN)

– Simple network configuration

– Data security and fault tolerance

While the advantages are meaningful in many implementations, the disadvantages may be what are holding some organizations back from accelerating their cloud-native applications. For IT organizations where budgets are flat but capacity demands are increasing, or where you are having challenges balancing scale and performance for cloud-native applications, DAS and the associated technologies may be outdated and no longer capable of supporting your storage needs.

Direct Attached Storage (DAS) Disadvantages

– Data silos

– and high administrative costs

– Poor Scalability

– Poor flash utilization

– Long recovery times

– Applications are tied to servers

Let’s unpack each of these.

DAS Creates Data Silos

DAS is digital storage directly attached to the computer accessing it, as opposed to storage accessed over a network. DAS can consist of one or more storage units, such as hard disk drives (HDDs), solid-state drives (SSDs), or optical disc drives, within an external enclosure. Because storage is directly attached to the application server via a protocol like iSCSI, data analysis becomes more challenging because the data may be stored in formats that are inconsistent with one another. In many cases, DAS slows down data analysis because it’s more challenging to pool large datasets into a single analysis; outcomes are better when the application has access to ALL the data. Not having access to all the data from different parts of the business may degrade the return on investment (ROI) from collecting the data in the first place.

Overprovisioning Comes at a High Cost

Many organizations are moving to disaggregated storage that delivers the same performance, latency, and IOPs as local drives. Why? Because you can achieve the same levels of local NVMe-flash block performance, but the applications are no longer affected by drive failures. Block volumes, of course, can be any size, and they’re thin-provisioned. That’s a big thing. When using DAS, someone, usually human, must choose what size drive you’ll put in every host. And that human is going to choose a 4 or 8TB drive. And if you’re a storage administrator, you never want to be the person who picked the drive that’s too small. So, you’re always going to err on the side of having some capacity cushion. But using larger drives will make poor flash utilization even worse. Deploying software-defined storage that supports block volumes of any size and that grows in response to business demands is a big deal. It’s also beneficial if server failures are covered this way. When the drive is local, if the server fails, that drive is also unavailable. But disaggregated storage that offers the same performance as local storage means server failures affect the application, so the application has to move. But it can be restarted at an alternate host and pick up where it left off. Which means that if you are doing even application-side recovery with a server failure, you can restart the application elsewhere. And instead of having to synchronize the entire contents of the drive, or everything that had been written to a drive, you only have to synchronize the data that was missed while that application was offline. So your recovery can be in seconds or minutes, rather than hours or days, depending on the network. This is huge for cloud service providers (CSPs), because of the higher uptime, it affords them the ability to increase their service level agreements to their end customers.

Poor Scalability

How can you scale local DAS? The only way to scale local DAS is to swap a drive for a larger one or add more drives. But if you add more drives, the only way you’re going to be able to access them is if you can use them individually, or if you add software RAID or logical volume management on top of that. And that is a per-host configuration. With a software-only, disaggregated solution, you can scale storage completely independently from compute, and vice versa. Meaning that if you need more compute in your environment, you can scale the compute independently. If you use DAS, and you’re keeping everything the same, and you need more compute power, every time you add a node, you add another drive. And so, if you didn’t need more capacity or were already underutilized, adding more drives compounds your underutilization problem. It’s important to understand that independent scaling of capacity and performance is a consideration when managing the efficiency and utilization of your flash investment.

The Benefits of Disaggregated, Software-Defined Storage versus DAS Storage

– Host/applications don’t see drive failures: well, a Mongo database can, especially if it’s on three different servers and doesn’t need the storage to be highly available. It can handle a drive failure and replicate by itself. But just because something can be done doesn’t mean it should be done. Because that would mean an application architect has to account for high availability and data protection, as well as just the fact that you want a document database. So it forces people to think about data protection. But application developers don’t want to have to worry about data protection. This means that when a drive fails, the application is unaffected, versus the application going offline and having a replacement driver, which is more likely moving the instance to a different server, where you would have to go ahead and the application will go ahead and rebuild a new empty drive, transferring all that data over the network. So not seeing drive failures is a big plus here.

– Volumes are not limited (in size) by physical drives: the counter to this is just using LVM, or MD and stripe across drives, or forming a RAID group. Which is all possible, but with DAS, you have to do that on a per-host basis. So, it’s really not a good solution.

– An application host failure also kills the volume (drive) – applications can be restarted elsewhere: An application host failure doesn’t kill the drive. If you’re using DAS, and you have a host failure, you have a power supply blowout, which takes the server offline, which means the drive that was part of the three-way replica is also offline. And think of it: it’s not just that you’d have that drive down; the two surviving replicas will be in a degraded state, especially if they start up another instance and start replicating. So, replicating can really hurt application performance. But if a host fails and the application instance is restarted on a different host, it will only do recovery. Even without 2x or 3x replication, recovery is only going to be for the amount of time the drive or application has been offline, rather than, like DAS, recovering an entire 4TB or 8TB drive.

– QLC drives can be used without worrying about the application write IO patterns: QLC drives require you to write to them in a special way. If you don’t want to wear out a QLC drive, you have to write to it in large blocks. For the current batch of Intel drives, which are called 16k indirect units, any multiple of 16 is fine. So in future drives, they’re going to move to 32k or even 64k, and future drives, indirect units. What does an indirect unit mean? It means that the drive internally wants to do an erase operation on at least the size of the indirect unit. So, in 32k or 64k, it basically means they want to do operations in 64k chunks. So, if you do a single 4k write, you may invalidate an entire 16, 32, or 64k range on the drive. Which means that when the drive goes into garbage collection, it coalesces reads from different areas, writes them to a new region, and erases an entire cell. It’s going to wear the drive out really fast. The 4k write operations are just terrible for the drive. So, if you use inexpensive NAND and have a drive in each host, for DAS deployments you have to worry about your applications’ write patterns. If you are a service provider, you can see how this doesn’t work. If your service provider doesn’t know what the end customer will use, you can end up wearing out your drives. With disaggregated, software-defined storage, it takes writes and completes them in Optane memory addressable space, and doesn’t write to NAND until it writes in a large block form factor today, which is 32k. So it increases the endurance of QLC NAND flash.

– No one overprovisions storage: With DAS, I mentioned this earlier, no one wants to be the person who said, “Oh, I’m the one who said we should use 4TB drives in each host.” And the application team ends up saying, “Oh, we really need 5TB drives, or we need 6TB of space.” So everyone’s going to go ahead and err on the side of a larger drive, which is more wasteful.

– Data protection, compression, and size per volume are managed in a central location: a local drive is not, by definition, protected against a failure. Lighbits offers different levels of data protection; we compress the data. So if you turn compression on, we save space by compressing the data. And all of this is managed in a central location.

Multi-tenancy can be supported (vs. a local physical drive). Many organizations need to support it. Generally, permissions on a local drive on the device are set so that the drive is either accessible or not. So, it becomes much more challenging to support multi tenancy on a single local drive; there are definitely ways to do it. But for the most part, multi-tenancy is an aspect of us being a complete system and a complete storage solution.

– Failure domains are possible without application awareness: if you’re going to deploy Mongo or Cassandra on a three-rack system, you have to understand from the application level about where that gets deployed, and your different failure domains. Lightbits supports the failure domains by tagging the storage. Then you have failure-domain protection for the storage, built into the centralized system without the application having to be aware. So the application can then proceed to fail and move elsewhere. And the data, if you had a 2x or 3x replica model, will still be available.

– Rich data services without application stacking and/or local host configuration: There are a lot of things you can do with Linux. Lightbits protects against a drive failure with elastic RAID. If you are doing DAS, you would have to use Linux LVM or Linux MD to create RAID6, but you would have to do that on every single host, and you would have to manage that configuration on every single local host. And then that data is still only available to that host. Even if you made your own NFS server, an iSCSI target, a SPDK NVMe-oF® target, or a kernel-based NVMe over fabric target, you could still make a RAID configuration, but it would still be for a single target. There’s no HA there, and you don’t have multi-pathing. The data is still only available to that one host, and if that host goes down, your data will be completely offline. This is a strong reason why a clustered solution is better than DAS.

Direct Attached Storage (DAS) Out-of-the-Box

What do you get out of the box with DAS? You get a block device. Period. You get a block device that performs at low latency and fairly high bandwidth, because it’s one device, the limits of one PCIe device. But it’s just a block device; it doesn’t do anything else out of the box. When you use that block device locally on the application host, it simply provides a very fast block device.

What you don’t get with DAS out of the box are rich data services at NVMe speeds. While you may get thin provisioning, snapshots, and clones. You don’t get them at NVMe speed, and they aren’t instantaneous. And you don’t get consistent response times. Your application may typically experience 80 to 100 microseconds of read time when the drive is in garbage collection, which may jump to 200 or 300 microseconds, depending on the drive type and the controller’s power. This inconsistency over time means the application doesn’t behave consistently. With a clustered solution, you’ll get all these benefits, but with a block device like DAS, you won’t get these:

Data Services:

– Logical volumes w/online resize

– Thin-provisioning

– Inline compression

– Space/time efficient snapshots

– Thin clones

– Online SSD capacity expansion

– High performance and consistent low latency

High Availability and Data Protection:

– NVMe multipathing

– Standard NIC bonding support

– Per volume replication policies

– User-defined failure domains

– DELTA log recovery (partial rebuild)

– SSD failure protection ElasticRAID

– Highly available discovery Service

– Highly available API service

Frequently Asked Questions on DAS Storage

- Is DAS faster than NAS? In most common implementation scenarios, yes. DAS generally offers higher performance and lower latency because it does not have to deal with network congestion or the overhead of network protocols.

- Can multiple computers access a DAS at the same time? Technically, no. Because DAS lacks a network controller to manage simultaneous requests, it is designed for a 1-to-1 relationship with a host. Many users have discovered a workaround, which is to share a DAS drive over a network using the host computer’s operating system (e.g., “Windows File Sharing”). However, if the host computer is turned off, the storage becomes inaccessible to everyone else. For true multi-user access without a host PC, a NAS is required.

- How does DAS differ from NAS and SAN?

| Feature | DAS | NAS | SAN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connection | Direct (USB, SAS) | Network | Dedicated Network |

| Nodes | Usually 1 | Multiple | Multiple |

| Implementation Setup | Simple | Moderate | Highly Complex |

Additional Resources

Cloud-Native Storage for Kubernetes

Disaggregated Storage

Ceph Storage

Persistent Storage

Kubernetes Storage

Edge Cloud Storage

NVMe® over TCP